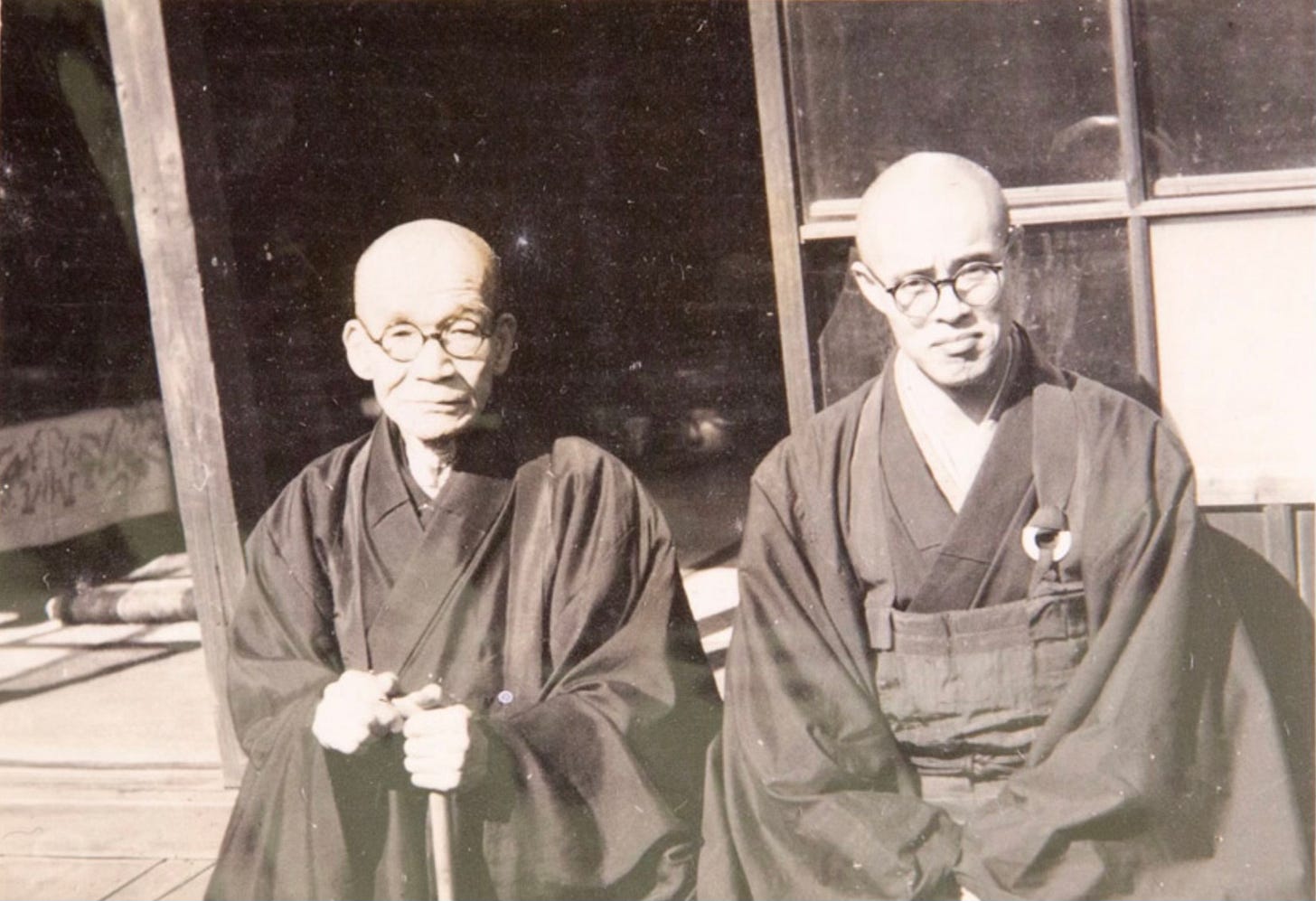

From Tokugen Sakai

(Sawaki Roshi with Tokugen Sakai)

Zen Master Daichi (1290-1366), often associated with the poetry he wrote, is considered one of the greatest poets in the Japanese Sōtō Zen tradition. His poems have become synonymous with Zen verses, to the point where being able to recite it from memory was once a common expectation of Sōtō monks. Thus, almost every novice monk could effortlessly recite stanzas from Daichi’s verses. In other words, for generations, Sōtō monks have used these poems to elevate their own spiritual state as well as part of their emotional and moral education. There is no other example of poetry that would havesuch a profound influence on later generations.

The verses of Zen monks in Sanskrit are called gāthā (Jpn. geju), the term usually used for metrical compositions in Buddhist scriptures. In this respect, Zen poetry referred to as gathas, or verses, is something that distinguishes it from regular Chinese poetry (Jpn. kanshi). Sawaki Roshi is fond of these verses, and he has likely given countless lectures on them up to the present day, perhaps even losing track himself.1 I have been practicing with him for twenty-three years now, and during that time, I have participated in these teachings more than sixty or seventy times. As a result, I have now memorized these verses by heart. Anyone who has been practicing with Sawaki Roshi for more than ten years would have heard his lectures three or four times at the least. There is no one else who has studied and taught these verses as extensively as Sawaki Roshi. Although it cannot be stated with absolute certainty, the lectures which form this fourth volume of Roshi’s complete works seem to date back to the wartime period, specifically during the time when he taught atTengyō Zen’en, or Heavenly Dawn Zen Garden era at Daichūji in Tochigi Prefecture, from October 1940 to September 1944.

The reason why Sawaki Roshi gave so many lectures on these verses is connected to the issue of his own character formation. In other words, Daichi’s verses were not merely literary works but expressions of his relentless commitment to the practice of the Buddhist path. Consequently, these verses have always been familiar to the monks practicing with Sawaki Roshi, not only because of their outstanding literary quality but also because they vividly capture a life of pure and devoted practice. It is well known that Sawaki Roshi neither wrote essays nor composed verses himself, yet he studied these verses extensively. This was because, through these verses, he was engaging in the study and practice under the ancient Buddha Daichi, whose spirit lives on eternally within the words.

Sawaki Roshi was ordained in 1897 at Sōshinji, a temple located in Kumamoto Prefecture, marking the beginning of a lifelong journey of practice and pilgrimage. In 1916, he was invited to be the leader of monks at Daijiji, the largest Zen training monastery in Kyushu, on the outskirts of Kumamoto. Roshi stayed in Kyushu for nineteen years, from the age of thirty-seven to fifty-six, until he became a professor at Komazawa University in 1935. For roshi, Kumamoto became a second home, and because of this, people often mistakenly think he comes from Kumamoto.

Daichi was a Zen monk from Kumamoto, who ordained and took the tonsure under Kangan Giin (1217-1300), the founder of Daijiji. Because of this connection, Sawaki Roshi felt a deep interest and a sense of local affinity toward Daichi, dedicating many years to his study. Rōshi even went so far as to personally investigate all the historical sites associated with the master. He actively lectured on Daichi's verses throughout Kyushu, introducing his teachings and character to the local population. This led to a growing movement to honor Daichi in Kumamoto Prefecture, especially in the Kikuchi District, where prominent local figures organized visits to the historic site on Mount Hōgi.

The verses vividly express the life of Daichi, as there is nothing quite like poetry to reveal the inner aspects of a person. Daichi's verses are of no exception, resonating with the vibration of a religious life. By lecturing on these verses, SawakiRoshi was, in a sense, continuing his own practice of self-cultivation through Daichi. Consequently, there is a significant presence of Daichi's spirit within roshi's own life. In this sense, the lectures on the verses serve as valuable material for understanding the formation of Sawaki Roshi's character.

To appreciate Zen verses is to learn from the religious life of their authors, rather than merely receiving them as written words. While there are some compositions that bear the name of Zen verses but amount to nothing more than wordplay, for a true practitioner of the Buddhist path, such works are nothing more than idle ornaments. As Dōgen said, “Even if one has not yet generated genuine bodhicitta, we should imitate the dharma of the buddha-patriarchs who previously generated bodhicitta.” Learning from the practice and life of those who came before us—this is the essence of Buddhist practice. Since ancient times, in the Zen tradition, the study of an individual’s practice has often been facilitated through their verses, which serve as a fitting medium for such learning.

This was exactly the case for Sawaki Roshi as well—his own practice was shaped through the verses of Daichi. In his dharma talks, Daichi was brought to life. In other words, through delivering his teachings, Daichi must be studied and embodied; it must not be a mere introduction of the verses alone.

Sawaki Roshi deeply devoted himself to the dharma of Daichi, recognizing him as a true predecessor in the authentic transmission of Dōgen’s teaching. For this reason, wherever and whenever he was, he would always recite Daichi’s Verse of Vow (Jpn. Hotsuganmon). No other text was ever recited by him.

It is said that the Verse of Vow was originally composed by Kangan Giin, the ordination teacher of Daichi. Daichi recited it throughout his life, making it the vow of his own Buddhist practice. For this reason, over time, people naturally came to refer to it as Daichi Zenji Hotsuganmon. This written vow must, in essence, serve as the vow of those who seek to learn from Daichi. It is thus understandable that it became the backbone of Sawaki Roshi’s life of seeking the Way.

Let us now recount the life and practice of Daichi himself. It is said that the he was born in 1289 to a farming family in Nagasaki, Shiranui Town, Uto District, in what is now Kumamoto Prefecture. At the age of twelve, he shaved his head and entered the Buddhist path under Kangan Giin at Daijiji, located in present-day Nodamachi, Kumamoto City.

Kangan Giin (1217-1300) is said to have been the son of Emperor Go-Toba’s youngest child—though according to another account, the son of Emperor Juntoku. At the age of sixteen, he left home and was ordained on Mount Hiei. In 1241, at the age of twenty-five, he left the Tendai establishment and became a student of Dōgen at Kōshōji in Uji. In 1244, he traveled to Song China, where he journeyed extensively through various regions, visiting and learning from renowned monks and masters of the Five Mountains Ten Temples system.2 After ten years of diligent practice and study, he returned to Japan in the summer of 1254, the year following the death of Dōgen. In 1264, carrying with him the recorded teachings of Dōgen, he once again travelled to China. There, he introduced Dōgen’s writings to various Zen masters in different regions and received prefaces from them. He returned to Japan in 1267. Thereafter, he remained in the region of Higo,3 dedicating himself to the development of this remote area and to the spiritual guidance of the common people, to which he devoted his entire life. Daijiji, the site associated with him—also known by the honorary title Zen Master Hōō (“Dharma Emperor”)—continues to shine with the light of the Dharma even today, serving as the head temple of the Kangan lineage and a central training monastery in Kyushu. Daichi was a disciple born of the teaching and guidance of Kangan Giin. He entered the Buddhist path under Kangan Giin at the age of seven, when the elder master was already in his twilight years at the age of seventy-seven. The old master passed away a few years later, on August 21, 1300, at the age of eighty-four. Thus, Daichi spent about five years of his early childhood under his direct tutelage. Although this was a brief period of instruction, it laid the essential foundation for Daichi’s entire life.

There is a legend about the moment when this young boy first met old Kangan. At their initial encounter, Kangan Giin asked him,

“What is your name?”

The boy replied,

“Manjū” (which sounds like both a personal name and the word for a sweet bun).

The master then picked up a sweet bun that was in front of him and gave it to the boy, teasing,

“A Manjū eating a manjū— how do you explain that?”

The young boy looked straight at the master and replied,

“It’s like a large snake swallowing a small one.”

Astonished, the master said,

“You are wise. I shall name you ‘Shochi’ (Small Wisdom).”

However, the boy refused, saying,

“Small wisdom hinders enlightenment. Please call me ‘Daichi’ (Great Wisdom).”Kangan laughed and said,

“Very well, I shall call you Daichi.”

Though this is likely a fabricated tale, it serves as an excellent anecdote for understanding the character of Daichi.

In the year following the passing of Kangan Giin—when Daichi was thirteen years old—set out on a pilgrimage. He was searching for guidance in practice from various teachers. He first traveled to Kamakura, then the cultural center of Japan, where he met Nanpo Shōmyō (1235-1308) at Kenchōji. From there, he journeyed across the country, seeking out masters. For a time, he stayed at Hōkanji in Yasaka, Kyoto, under Shaku Unseidō, a disciple of Kangan Giin who had received precepts from him. He then continued on to Daijōji in Kaga, in the Hokuriku region, where he sought out Keizan Jōkin, the fourth-generation heir of the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage. Daichi studied under Keizan for seven years, during which he firmly established himself on the path of Dharma and reached an unshakable realization.

After practicing under Keizan and realizing the authentic Dharma of the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage, Daichi, at the age of twenty-five in 1314, resolved to undertake the great endeavour of crossing to Yuan China to deepen his practice. At that time, the leading Zen masters in China included Gulin Qingmao (Jpn. Kurin Seimu; 1262-1329), Yunwai Yunxiu (Jpn. Unge Unshū; 1242-1324), Hongfeng Mingben (Jpn. Chūhō Myōhon; 1263-1323), and Wujian Xiandu (Jpn. Muken Sento; 1265-1334). Daichi traveled widely to visit these eminent teachers, explored sacred sites and historical places, and immersed himself in the culture of the Yuan dynasty. After eleven years of study abroad, he returned to Japan in 1324. The verse he composed at that time is well known and is said to express his spirit and determination—“though China is rich and abundant, not a single man is worthy to be taken as a true teacher of the Dharma. Better to roll up my robes and return home.”

His eleven years of seeking teachers and the Dharma in Yuan China ultimately proved fruitless, for he found that not a single master there surpassed Keizan in Japan. It is said that his efforts ended in vain.

Since ancient times, the Japanese have tended to be overly enamoured with foreigners and foreign cultures, often losing their own sense of self under their spell. This tendency remains unchanged even today, and it seems that even the Zen masters who once traveled to Song China were no exception. Most who traveled to China accepted what they found there uncritically, and upon returning to Japan, proudly proclaimed it as their own. Many Chinese monks also came to Japan, and due to this national tendency, they were often treated with great favor. In contrast, Daichi possessed a keen eye for discerning true Dharma. Observing the corruption and decline of the Buddhist world in China at the time, he became disillusioned and chose to return home. As a result, the verse he later dedicated to Japanese monks aspiring to study in Yuan China is truly exceptional and unconventional:

Cold and warmth—

only you can know them for yourself.

How could a true man of resolve be deceived by others?

Do not take the noble pure gold of Japan

and return having bartered it for the brass of the Great Tang.

In this verse, we can sense how deeply Daichi resented the lack of integrity and excessive servility displayed by many of the monks studying abroad at the time. What, then, enabled him to open such a discerning eye? It was none other than the rigorous training and true guidance he had received before his travels—from his authentic teacher, Keizan Jōkin. This is evident from the fact that in his verses, we find three poems entitled “To Venerable Keizan” and eight poems titled “Mourning Venerable Tōkoku.4 These clearly show how much Daichi’s character and spiritual formation were owed to Keizan.

Upon his return to Japan in 1324, Daichi landed at Miyadono in Ishikawa District, Kaga Province—present-day Kanaiwa in Kanazawa City. Once ashore, without hesitation or delay, he felt he should first return to his revered teacher, Keizan, who was then residing at Tōkokuzan Yōkōji in Sakai, present-day Hakui City, Ishikawa Prefecture.

The biographer records the following exchange between master and disciple at that time. When Daichi arrived at Tōkokuzan, it happened to be during the evening assembly. Keizan, seeing his beloved disciple only recently returned from abroad, asked him:

“When a child returns home and meets his parent, how does it feel?”

Daichi replied,

“Before an old mirror stand, there is no lamp.”

Keizan then asked,

“Even without a lamp, can anything be reflected?”

Daichi answered,“It certainly reflects—but it cannot show the future.”

Upon hearing this, Keizan said with joy,

“You are a true heir to our lineage.”

This dialogue offers a glimpse into the depth of their personal and spiritual relationship.

Within just a few generations after Keizan, the core principle of the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage—“nothing to attain,” “no enlightenment to realize,” “just sitting”—came to be distorted. It was confused with the Chinese Sōtō Zen of the Sōzan line, and in some extreme cases, even degraded into a derivative form of Kanna Zen (Zen of kōan introspection). Amid such circumstances, Daichi stands out as one of the rare individuals who inherited the pure Dharma of the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage and proclaimed it without any trace of deception or distortion. The two works attributed to his later years—Daichi’s Dharma Talk (Jpn. Daichi Hōgo) and On Practicing Throughout The Day (Jpn. Jūniji Hōgo)—clearly testify to this fact. In his time, there was no other Zen figure who articulated the Dharma with such clarity and thoroughness.

“When it comes to resolving the great matter of life and death, there is no path more essential than zazen. To do zazen, place a cushion in a quiet place and sit upright upon it with correct posture—doing nothing with the body, uttering no words with the mouth, harbouring neither good nor ill within the mind. One does nothing but sit in stillness, facing the wall, and thus passes the days in seated repose. Beyond it, there is no special or mysterious meaning to be sought in it.”(from “Daichi’s Dharma Talk”)

Such bold words are rarely found elsewhere. Daichi was born forty-seven years after the death of Dōgen, yet he was the legitimate Dharma grandson in the direct Eihei Dōgen’s lineage.

Later, under the guidance of Keizan, he received Dharma transmission from Keizan's own Dharma heir, Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350), and thus became the sixth-generation ancestor in the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage. In the first month of 1333, Meihō formally transmitted to him the so-called “robe passed down through the six generations”— the lineage passed down from Dōgen, the first patriarch of Eiheiji, through the second, Ejō; the third, Tettsū Gikai; the fourth, Keizan; and the fifth, Meihō – along with an accompanying Dharma certification. At that time Daichi composed the following poem:

I humbly receive and bear the entrusted Dharma of the Great Master Onkō,5

Here within the Rooster’s Foot Peak.6

In the ancestral chamber, the lamp of transmission is unbroken.

At the assembly beneath the dragon flower tree,7

I shall not fall behind the true lineage of the Mind School.8

At that moment, Daichi was deeply moved, and his profound gratitude took the form of a verse dedicated to his compassionate teacher and ancestor, the venerable Keizan. This verse has been preserved among the Daichi’s Verses.

To Venerable Keizan

The robe passed down through six generations now rests upon this humble monk.

For a thousand years, I have traced the footsteps of Huineng in the Southern Peaks.

Through long days of labour, I have honed my practice—

Now, may I raise aloft the undying lamp of the Buddhadharma,

its flame shining bright in the ancestral hall.

At that time, Daichi left the guidance of Meihō and entered a secluded hermitage deep in the mountains below Hyakuzan, in Yoshino Village, Kawachi Manor. In time, practitioners who admired his way began to gather around him, and it was decided to establish a temple there. This was the beginning of Shishizan Gidaji.9 After residing at this temple for less than ten years, he quietly passed on its leadership to a disciple and brought his life in Kaga to a close. Then, without fanfare, he returned to his native land of Higo. He was nearing the age of forty. It was from this point on that Daichi's true life of teaching began, and the majority of his poetic verses were composed during this period.

This was the era of the Northern and Southern Courts, a time when the realm was torn in two and fierce, bloody battles were waged in constant succession. Even among the powerful clans of Kyushu, many were divided by shifting political tides, turning upon one another in violent conflict. Most of them, however, were opportunistic— concerned above all with self-preservation. Amidst such turmoil, the Kikuchi clan stood apart: steadfast in their unwavering loyalty to the Southern Court, they held firm without ever compromising their principles.

Daichi accepted the devotion of Kikuchi Taketoki—the 12th head of the Kikuchi clan, who, upon entering the way, took the name Shinkū Jakua—and in 1330 founded Hōgizan Shōgoji in a secluded valley deep in the mountains of Higo. The temple stood upstream along the Hazamigawa River, in the remote region of Hatajiguchi-yama, Anagō, Kikuchi District.10 At this time, Daichi was forty-one years old, and Taketoki was thirty-nine. It is said that the master remained in the remote mountain valley for twenty-one years, never once going down from the hills.

During those two decades, the Kikuchi clan passed through four generations: the 12th lord Taketoki (Shinkū), the 13th lord Takeshige (Jakuzan), and the 14th lord Takemitsu (Jakua). It was a time marked by unceasing warfare, yet throughout it all, Daichi served as the clan’s spiritual cornerstone and unwavering support. Their lives were marked by constant upheaval—what existed today offered no guarantee for tomorrow. Yet their aspiration for the Way burned with intensity, and Daichi, in turn, rose to meet their fervent hopes with equal depth. That their spiritual communion was no ordinary bond is evident from the many vows they offered to their master, several of which still survive today as part of the Kōfukuji documents.

However, Daichi’s method of guiding others was fundamentally different in character from the fully staged, performative style that Mugaku Sogen11 employed with Hōjō Tokimune. Daichi’s Dharma Talk (delivered in 1336 to Taketoki [Jakua] – not to Jakuzan, as some mistakenly claim) and On Practicing Throughout The Day served as foundational teachings for the spiritual guidance of the Kikuchi clan. These two Dharma texts clearly indicate that members of the Kikuchi family undertook formal periods of retreat at Hōgizan, during which they earnestly engaged in monastic life in accordance with the pure regulations of the Zen school. These Dharma words transmit the authentic shikantaza, or just sitting—Zen of the Eihei Dōgen’s lineage in its purest form, and are unparalleled in their clarity and fidelity. They are invaluable for understanding the character of Daichi’s style of Zen. Within the Keizan lineage, where elements of popular religiosity had begun to intermingle, Daichi stood out in his refusal to compromise. Holding fast to pure Zen alone, he remains a figure of true greatness.

Among the extant records that most vividly convey the inner life of the Daichi’s practice are the verses from “Living on Mt Hōgi” series. In an age of turmoil, the attitude of serene and undisturbed living expressed in these poems reveals nothing less than the embodiment of living Buddhadharma. It is this very reality—lived and quietly manifested – that appears to have moved and inspired the Kikuchi clan so deeply.

It seems that what especially drew Sawaki Roshi to the Daichi’s verses was precisely this group of poems composed during Daichi’s mountain retreat. In a lecture given to the students of the former Fifth High School— young, headstrong, and full of rebellious spirit—he presented and expounded on one such gāthā:

Burning incense, I sit alone beneath the tall pine tree.

The wind blows, and the cold dew wets my robe.

It’s dawn when I rise from meditation and head off down the valley.

I’ll bring back the remaining crescent moon scooped up in my pitcher.

This verse stirred the blood of the young listeners. At the time, Sawaki Roshi himself was living a solitary mountain life in a hut atop Mannichi-zan, so the sentiments of the poem must have resonated with him deeply as lived truth. It’s said that in the student dormitories of the Fifth High School, the lines of this verse were written boldly – one character per glass panel of the sliding doors—and even scribbled onto the walls, leaving behind traces of the fervour it inspired.

In 1351, at the age of sixty-two, Daichi moved to Shiyōzan Kōfukuji in Ishinuki Village, Tamana District, at the request of Kikuchi Takeju. Later, he proceeded to Suigetsu-an (Water and Moon Hermitage) in Takaki District, on the Shimabara Peninsula, where he would eventually settle. This became the place of his passing. On the tenth day of the twelfth month in 1366, at the age of seventy-seven, the life of this great Zen master came to its end.

There remain two collections attributed to Daichi: one is a surviving volume titled The Verses of Zen Master Daichi, and the other is a secondary compilation known as Record of Miscellaneous Verses. The former—commonly referred to and widely known as The Verses of Daichi—contains 229 verses. The latter one consists of an additional thirty verses that were compiled separately. The Verses of Daichi, was most likely compiled by his disciples—perhaps including figures such as Kōgen and others—and was published in the mid-Muromachi period. It seems to have been widely known from a relatively early time. Entering the Edo period, it was carved and printed from woodblocks no fewer than nine times, each instance accompanied by a reissue of the text. From this, one can clearly see how deeply cherished and widely used these verses were within the Zen monastic world of that era.

When we examine the 229 verses preserved in this single volume, it becomes clear that they are in fact a record of Daichi’s lifelong path of practice and realization. It is only natural that any account of Daichi’s spiritual journey would be inseparable from these verses. For those reading Sawaki Roshi’s commentary on Daichi’s Verses, I would not recommend approaching them with the mindset of composing refined Chinese poetry. Rather, I encourage readers to receive the teachings with sincerity—reading the commentary simply and openly, and taking it to heart as spiritual nourishment for one’s own daily life. If one becomes overly concerned with poetic composition—focusing on tonal patterns, rhyming characters, or elegant diction—there is a danger of overlooking the true intent of the gāthā. A verse is a living expression, and as such, it ought to be received and appreciated with straightforward sincerity, just as it is:

“The snow that falls—grasp it, and it disappears; let it fall through the empty sky—and it is truly yours.”

As Dongshan Liangjie12 once said:

“The melodies of the Hu nation fall not into five-tone patterns; their harmony arises from the deep blue of the evening sky.”

In this, he spoke to the very purpose of verse and gāthā. The reader of Daichi’s gāthās is not called to analyse the structure or pursue rhyme, but rather to chant them with a heart at ease—and thereby awaken to the refined spirit of the Master himself.

Tokugen Sakai,

—an associate professor of Buddhist Studies at Komazawa University

The book containing Sawaki’s commentary, included in the fourth volume of the Sawaki Kōdō Complete Works, was first published in 1963, at a time when both Sawaki and Tokugen – the editor and author of the introduction – were still alive.

A formal system of state-sponsored Zen Buddhist temples in medieval Japan, particularly during the Kamakura (1185-1333) and Muromachi (1336-1573) periods. It originated as a hierarchical ranking of temples influenced by the Chinese Chan/Zen system and served both religious and political functions.

Now Kumamoto Prefecture.

Keizan’s posthumous name.

The term: “Great Master Onkō” refers to Mahakashyapa.

Mount Kurkihar, located between Gaya and Bihar. It is said that Mahākāśyapa entered nirvana here.

“The Assembly beneath the Dragon Flower Tree” refers to the future event when Maitreya descends into this world, attains enlightenment beneath the Dragon Flower Tree (Skt. nāga-puṣpa).

That is the Chan/Zen school.

From the name of the temple, Daichi is also known by another name: Daichi Gida.

Now Hanjaku, Kikuchi City, Kumamoto Prefecture.

(Chn. Wuxue Zuyuan, 1226-1286) He was a Chinese Chan master of the Linji (Jpn. Rinzai) school who played a key role in the early development of Zen Buddhism in Japan, particularly in the Kamakura period. Became the founding abbot of Kenchōji in Kamakura, the first of the Five Mountains) system of state-sponsored Zen temples.

(Jpn. Tōzan Ryōkai; 807-869). One of the most important figures in Chan/Zen Buddhism and is best known as the founder of the Chinese Sōtō school.